The wartime pivot: managing the high-interest debt of market impact

Choosing between organisational health and market survival: the strategic trade-offs of the senior engineering leader in wartime

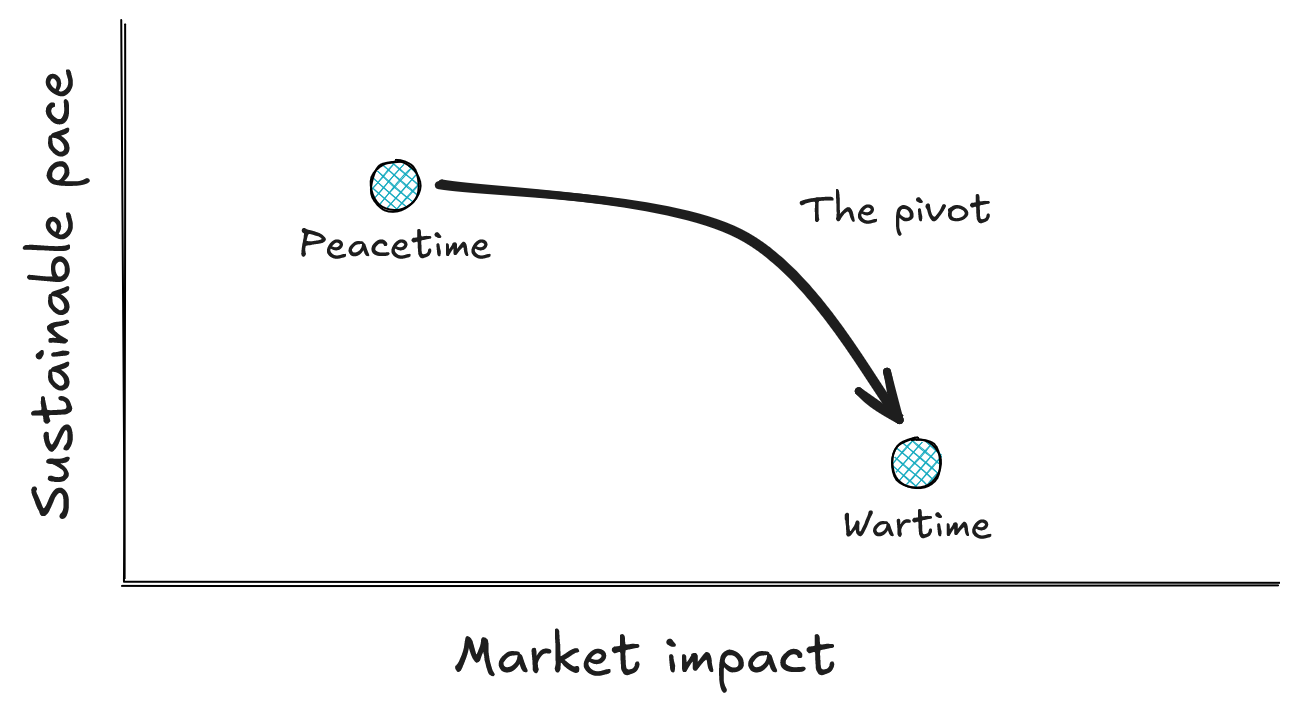

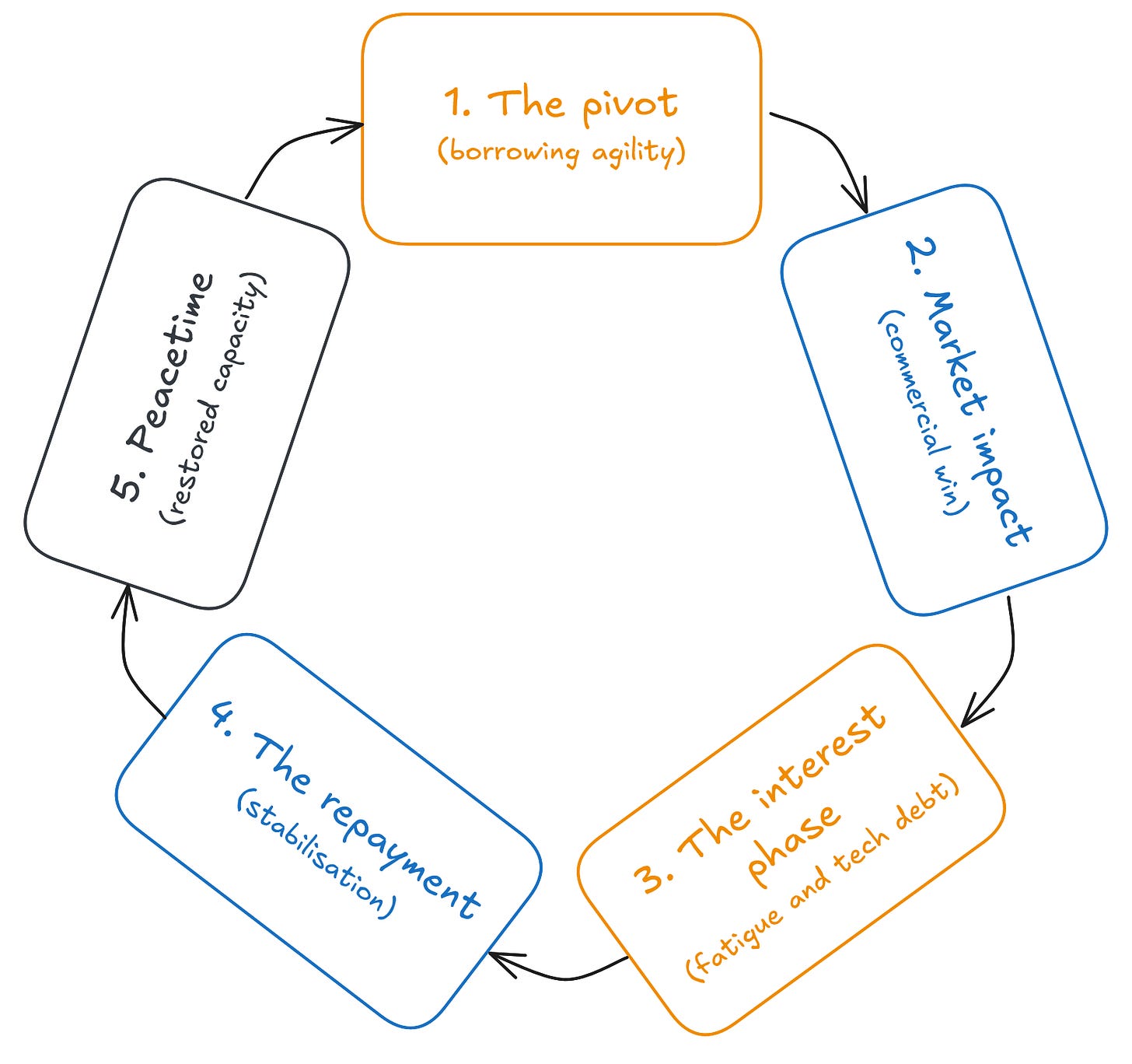

Engineering leaders often treat sustainable pace and flexible scope as universal constants. They are not. Mature leadership requires recognising when commercial pressure shifts an organisation from peacetime to wartime. In peacetime, we optimise for durability and long-term systemic health. In wartime, we must prioritise market impact by taking out a high-interest loan against our technical and cultural health.

I led this transition during Project Terry, a high-stakes integration with a major global partner (think Amazon or Netflix). We faced a non-negotiable four-month deadline for a six-month scope. Failure would have had a material impact on our annual objectives and blocked future expansion into new markets. To ensure total focus, I negotiated a six-month roadmap pause across my entire area, halting all non-critical development to meet this single commercial objective.

To maximise bandwidth, I replaced sync-heavy meetings such as all-hands meetings with lighter, async communication streams. I also delayed personal development time and the annual objective-setting cycle. These were not responses to team failure, they were strategic necessities to reduce communication overhead. While Engineering Managers initially pushed back to protect their teams, I bridged the gap between the team-level metrics and the global commercial requirements to ensure collective focus.

Operational focus

Effective wartime leadership requires a shift in organisational boundaries. This transition relies on three levers: strategic alignment, bridging the context void, and modified autonomy.

Strategic alignment

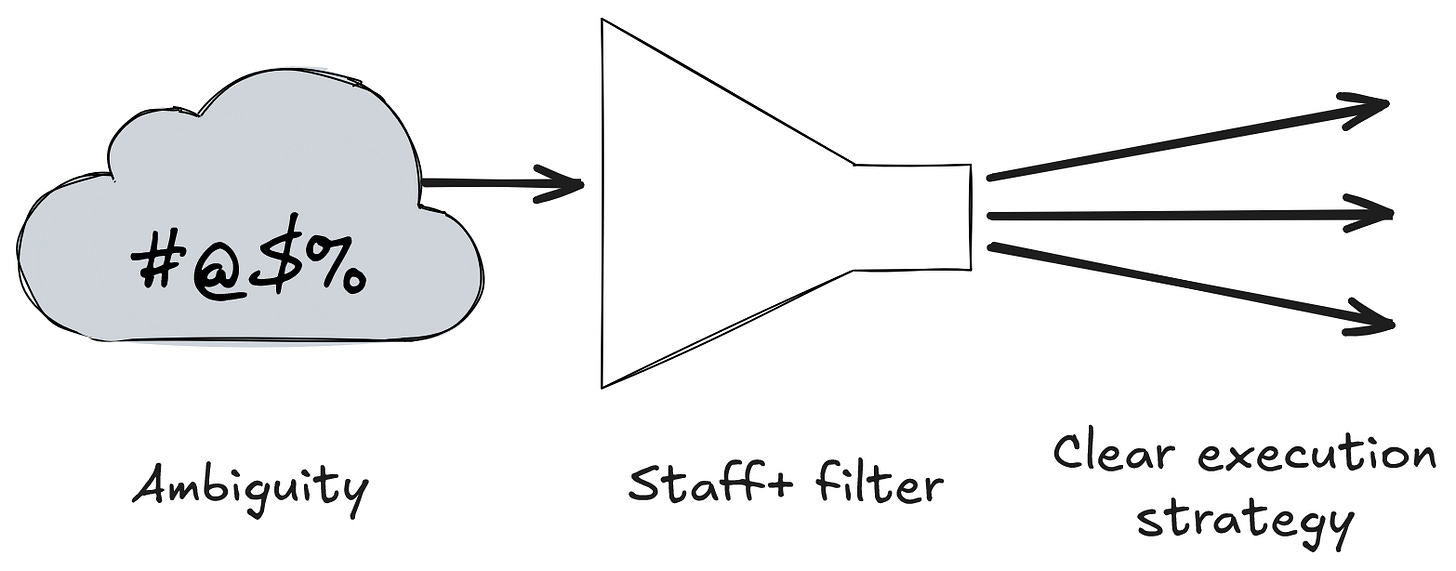

When requirements keep changing, timing is as important as transparency. I partner with Staff+ engineers to define technical red lines and identify strategic technical shortcuts before involving the wider leadership team. During Project Terry, I ring-fenced my managers, protecting their cognitive capacity for existing roadmaps until the delivery strategy was clearer. This ensured that when development started, the team was fresh and the execution path was defined.

Bridging the context void

When teams lack context regarding a high-stakes project, they fill the void with their own assumptions, often interpreting high pressure as management incompetence. To prevent this, leaders must treat teams as commercial partners. I bridged this by presenting company financial data to the entire area, translating abstract metrics into a language they understand. As the team understood the stakes, the project transformed from an arbitrary deadline into a shared mission.

Modified autonomy

Wartime delivery demands a shift from consensus to a disagree and commit model. In this mode, the cost of a delayed decision far exceeds the cost of an imperfect one. I negotiated a reduced feature set with Product and Design, stripping the scope to the minimum viable requirements for launch. This is when previous investment in building high-performing teams pays off, as the organisation relies on their ability to execute within tighter technical boundaries.

Navigating unknown unknowns: the dual-track strategy

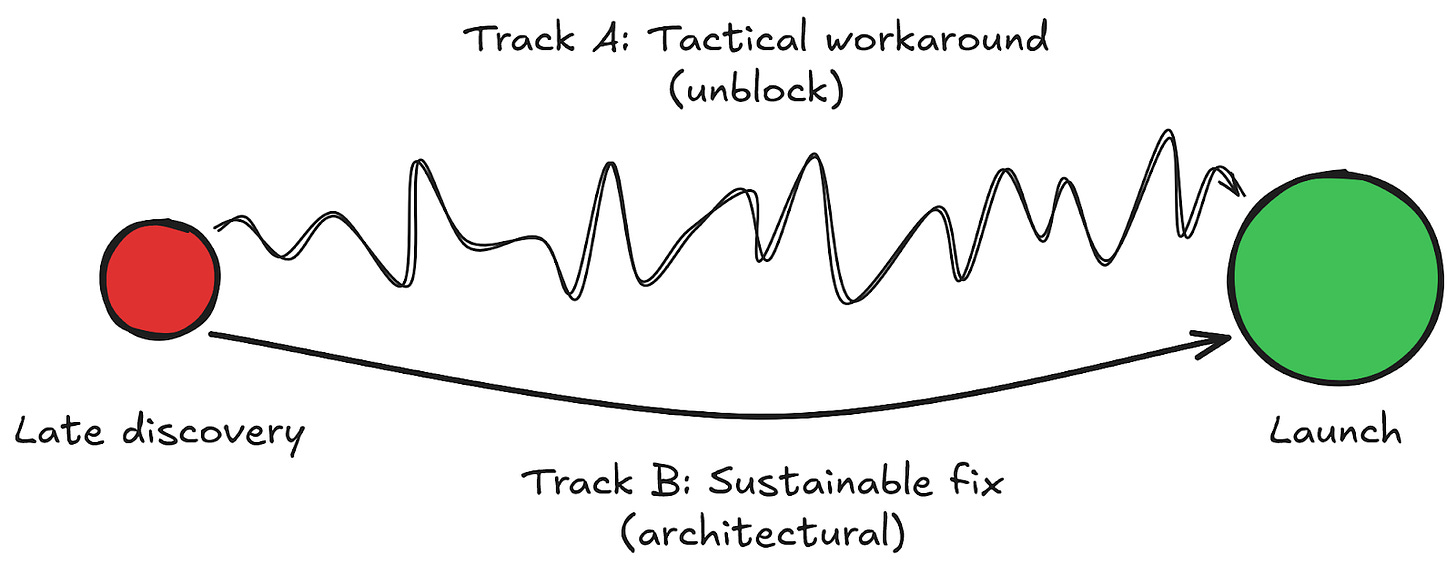

Linear problem-solving is a luxury that fixed-date delivery cannot afford. If a late discovery threatens the launch, you must be willing to pay for redundant paths to guarantee a successful outcome.

We faced this during the Terry integration when an incompatibility between our regional architectures and the partner’s account structure was discovered late. To mitigate the risk, we followed a two-track delivery model: one group worked on a tactical “quick and dirty” solution to unblock the launch, while another built the sustainable architectural fix. We accepted the waste of duplicate effort as an investment in delivery certainty. We maintained the discipline to abandon the tactical effort the moment the sustainable solution was confirmed. In wartime, the cost of redundancy is lower than the cost of failure.

Systems thinking also requires looking beyond the codebase. If software cannot meet a requirement in time, you must find an operational bridge. For features not ready for go-live, such as customer service tools, you may need to shift from technical requirements to a manual workaround, e.g. providing raw database queries for support staff or temporarily increasing operational capacity.

Maintaining high intensity for months inevitably creates emotional debt. A leader must proactively manage this by monitoring fatigue. During the Terry project, I maintained feedback mechanisms, specifically skip-level 1:1s, to monitor sentiment, allowing space for disagreement. I prioritised well-being through actions, such as approving immediate leave and ensuring efforts were reflected in talent reviews and promotions. Leadership in this mode is about holding a hard line on delivery while being radically empathetic toward the people carrying the load.

The recovery: paying the credibility debt

Wartime leadership is a high-interest loan against your culture. If the recovery phase is not managed with rigour, the result is permanent burnout and attrition. A leader’s responsibility during the transition back to peacetime is to pay down the technical and emotional debt incurred during the project.

Defending debt repayment

Strategic shortcuts are delivery loans that must be accepted by the business. During Project Terry, I ensured aftercare as a non-negotiable milestone, equal in priority to the launch itself. A mature leader must enforce this boundary. Allowing the business to skip the repayment phase destroys the team’s trust and turns the codebase into a liability. I treated the post-launch recovery as a hard constraint on the next quarter’s capacity, ensuring the system’s health was restored before the next cycle began.

The delivery addiction trap

The most dangerous side impact of wartime success is velocity addiction, where stakeholders attempt to normalise unsustainable output. I mitigated this from day one by categorising our intensity as a delivery loan, one with high interest rates. Throughout the project, I explicitly communicated that this pace was a response to a unique commercial moment, not a new baseline. Post-launch, I accepted a temporary dip in velocity, rejecting new high-priority requests to allow the system to stabilise and prevent long-term attrition

Restoring social capital

Restoring morale requires fulfilling every promise made during the wartime pivot. I prioritised the return to peacetime rituals: reinstating personal development time, approving holiday requests, and restoring standard meeting cadences. We closed the project with an in-person gathering to celebrate the success and hear from C-level leadership explain the specific commercial impact of the work to the teams. Fulfilling these promises is how a leader restores the trust required to ask for another extraordinary effort in the future.

Conclusion

Standard methodologies are tools, not canon. Agile or scrum should serve the business goal, not the other way around. The most valuable skill for an engineering leader is contextual awareness: recognising when the environment has shifted and having the courage to switch modes.

High-stakes delivery acts as a catalyst for leadership development. During Project Terry, I used the tight deadline as a stretch opportunity for a Staff Engineer to own the technical deep-dive across multiple domains. Apart from solving a technical problem, it also accelerated our succession planning by proving they could operate at a Principal level under extreme constraints. These projects are more than delivery milestones; they are high-pressure environments that build and reveal the next generation of leadership

Your value is not found in your loyalty to a process, but in your ability to shape that process to meet the commercial moment. Wartime is not a license to abandon discipline, it is a period to be more intentional where you choose exactly which risks to carry. True seniority is the ability to recognise when the constraints of a system have become its main liability, and having the strategic clarity to adapt the rules until the objective is secured.